|

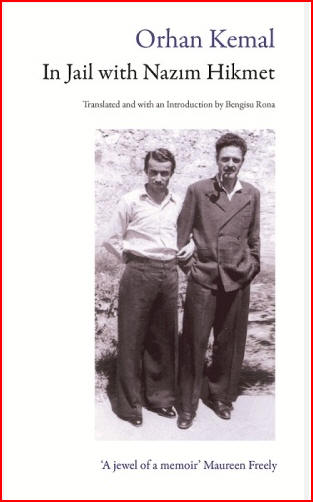

Orhan Kemal, In Jail With Nazim Hikmet

(London, Saqi Books, 2010)

Reviewed by Jennifer Mackenzie

Jennifer

Mackenzie is a poet, teacher and writer living in Damascus,

Syria. She received her M.F.A. from the University of Iowa’s

Writers’ Workshop, where she was a Truman Capote Fellow. Her

poems have appeared in a dozen American literary journals,

including Fence, Verse, and Quarterly West. She has also

published numerous articles in Forward Magazine, Baladna

English, and What’s On, all based in Syria. Jennifer

Mackenzie is a poet, teacher and writer living in Damascus,

Syria. She received her M.F.A. from the University of Iowa’s

Writers’ Workshop, where she was a Truman Capote Fellow. Her

poems have appeared in a dozen American literary journals,

including Fence, Verse, and Quarterly West. She has also

published numerous articles in Forward Magazine, Baladna

English, and What’s On, all based in Syria.

It is a rare work of non-fiction that makes the reader wish

to spend time in a Turkish prison. Yet moments of Orhan

Kemal’s memoir In Jail With Nazim Hikmet do just that.

Nazim Hikmet was and is considered to be the foremost

Turkish modernist poet of the twentieth century. As he was

also an unwaveringly vocal Communist, he was regarded as a

dangerous threat to Turkey’s political establishment, and

spent nearly 18 years in various Turkish prisons, where he

seems to have survived through sheer generosity. For three

and a half of those years, from 1939 to 1943, he was also

the cellmate and tutelary spirit of Mehmet Rasit Kemali, 12

years his junior, who was likewise imprisoned for Marxist

leanings. Indeed, it was in prison, in large part thanks to

Hikmet’s attentions, that Kemali emerged as the novelist

Orhan Kemal, as he chose to call himself. Under this

penname, Kemal rose to fame as one of Turkey’s greatest

novelists, in the course of his lifetime publishing 28

novels, 18 short story collections, and a number of film

scripts.

Kemal’s memoir sketches his formation as a man and writer

under Hikmet’s tutelage, as well as Hikmet’s own aesthetic

and personal development throughout this period. In 1938,

when he was sentenced to 28 years in prison, Hikmet had

published nine books of poetry and was already considered to

be the most important poet of his generation; just before he

was pardoned in 1950, he won – along with Pablo Picasso and

Pablo Neruda – the International Peace Prize. This longest

of his stints in prison also proved formative for Hikmet’s

writing, which evolved into the cinematic montage-style of

his masterwork, Human Landscapes Of My Country, an epic

based on the life experiences of many of Hikmet’s fellow

prisoners and their contemporaries.

In fact, it is one of the more interesting paradoxes of this

history – that is, the intersection of Turkish literature

and politics – that the same prisons which were intended to

suppress the production of unacceptable literatures

ultimately served as unorthodox conservatories for the

renovation of Turkish arts and letters. For besides setting

Kemal on his way to becoming an accomplished novelist,

Hikmet also mentored several other writers and artists, most

notably novelist Kemal Tahir and painter Ibrahim Balaban.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Hikmet’s own literary catalyst,

Vladamir Mayakovsky, also emerged from a revolutionary

background which shaped his emphasis on exuberant

destruction of old aesthetic as well as political forms.

Indeed, it is possible to credit the advent of Turkish

modernism to Hikmet’s exile in Moscow in the 1920s. As Kemal

records, Hikmet noticed one of Mayakovsky’s poems, with its

“smashed-up lines”, in a Moscow newspaper, was captivated by

the new style, and imported it to Turkey.

-

In her lengthy introduction, Bengisu Rona, a

professor of Turkish literature at SOAS, University of

London, is particularly eager to articulate this history –

in her words, “the way politics shaped the literary canon

and the extent to which the literary works reflect political

developments in Turkey.” She carefully enumerates the

regional geopolitics of the first half of the twentieth

century, and the vicissitudes communism underwent in Turkey

during this time. From 1920, when Ataturk telegrammed Moscow

requesting armaments and pledging cooperation in light of

the two countries’ efforts, “to save the oppressed from

imperialist governments,” to 1952, when Turkey joined NATO,

the Turkish government’s policy towards communism alternated

between wary, pragmatic tolerance and strict suppression.

And as official policy swung back and forth between these

two poles, Kemal and Hikmet, among others, lived out the

consequences.

Understandably, therefore, Kemal is equally keen to avoid

articulating this angle of political history in his memoir,

being acutely aware of the risks this would pose to his

freedom. As a child, he spent years in exile in Syria and

Lebanon after his father misread the political climate and

founded first one and then another opposition party. Later

on, Kemal’s association with Nazim Hikmet bracketed his own

experiences of prison. To begin with, though he had never

met Hikmet personally, one of the charges on which Kemal was

convicted in 1938 was a statement by a library clerk in the

town where Kemal was stationed that Kemal, “said he admired

Nazim Hikmet and that his works were valuable and should be

stored in the library.” Nearly 30 years after his release,

and three years after Hikmet’s death (in exile in Moscow),

Kemal was again arrested for allegedly, “believing in

revolutionary socialism, that is communism”, and forming an

illegal cell, “to engage in communist propaganda.”1

One major piece of evidence that was held against him was

the publication of Three and a Half Years With Nazim Hikmet,

as his memoir was titled in Turkish. This time, Kemal

successfully defended himself in court, saying the book was

a personal story, not “a eulogy for communism,” and he was

released a month after his arrest.

-

Kemal’s text focuses on his personal and

artistic connection with the older poet: his apprenticeship

to his “master”, as he called him. Throughout his early

twenties, Kemal wrote poetry prolifically in a derivative

style imitating Hikmet, whose popularity had led to his

being charged with inciting mutiny in the army and the navy

on the grounds that conscripts were reading his poetry.

Kemal was also charged with inciting mutiny, in the sense

that he was completing his obligatory military service when

he was reported to be an admirer of Hikmet’s work.

However, as he himself describes, when he meets Hikmet in

person during his second year in Bursa Prison, he is shocked

to find that his idol is not a statuesque, Parnassian

personage, but an ordinary man with bright blue eyes and a

smile like a child’s. Hikmet immediately takes the bookish

Kemal under his wing, and works methodically to shatter his

reliance on clichés. “All right, brother,” he tells Kemal

when he finally shares one of his own early poems. “But why

all this verbiage and – excuse the expression – mumbo jumbo?

Why do you write things you don’t really, sincerely feel?”

While Kemal’s first reaction is to feel “shattered” by the

criticism, he ultimately owes Hikmet a huge debt for

teaching him his craft. Besides insisting that Kemal learn

French, Hikmet strongly encourages him to abandon poetry for

prose, precisely because, having fewer preconceptions about

how it should sound, he has a much better chance of doing

something original in it. Most fundamentally, Kemal credits

Hikmet with teaching him how to see poetically. And in order

to train this capacity in himself, Kemal makes Hikmet his

primary subject of observation – Hikmet’s occasional

objections notwithstanding. At one point, the poet chastises

Kemal, while, “forcing himself not to laugh: ‘Look, at least

you could do it without telling me, so that I can behave

normally. Otherwise I shan’t even be able to move.’”

But Hikmet also employs, with far greater fluency and reach

during this period, the same method of sustained observation

and transcription of others’ stories to redefine his own

process of poetic composition. Besides tutoring any prisoner

who showed artistic aptitude, he invites many of his fellow

inmates to sit for lengthy portrait-painting sessions. As he

paints – whistling through his teeth, as Kemal recalls – he

also collects their life histories, which he then uses to

compose his masterpiece, Human Landscapes of My Country. In

aesthetic terms, the “psychological effect” he is seeking to

capture in his amateur portraits leads him to seek a new

formal imperative – a kind of documentary montage – in his

poetry.

This innovation seems so radical to Hikmet that he

eventually declares that he has, “stopped being a poet” and

become “something else”. From his early twenties, in good

Marxist form, he is in love with all facets of

industrialisation, from trains to cinematography, as the

material means of delivering production to the people. Once

in prison for the long term, Hikmet, then in his late

thirties, is exposed to a motley cross-section of Turkish

society. There he realises that, as editor Rona puts it,

“[their] life stories were a critical element in the

emergence of modern Turkey from the wreckage of the Ottoman

Empire,”2 – in other words, prime material for the kind of

history he wants to produce. And because he believes that

the writer is “accountable to the working masses”, he also

read the drafts of his poems to the other prisoners,

altering any parts they found false or confusing. Once,

after Hikmet shares one section of poem with its subject,

the man replies, “Master, what you’ve written is far closer

to the truth than what I told you.”

In the process of incorporating and elaborating these

perspectives in his poems, he invents a new form of

semi-collective epic. Whereas in European literatures, “the

lives of ordinary people … had been relegated to prose,”

they were, says poet Edward Hirsch, “essentially unclaimed

in Turkish literature at Hikmet’s time.” Thus, Hirsh argues

in his introduction to Human Landscapes, “[Hikmet’s] use of

such material places Landscapes at the source of modern

Turkish fiction as well.”3 Nor do the boundaries of Hikmet’s

imagination stop at the borders of Turkey; Kemal describes

how, before and during the Second World War, the prisoners

in Bursa huddle around a single radio, taking in the news.

Hikmet, besides battling with the pro-German camp, lives

this history vicariously, and incorporates the imagined

thoughts of German, English and Russian soldiers and

civilians into his epic.

-

For all the retrospective grandeur heaped on the power of

the imagination by editors and anthologies, both Kemal and

Hikmet remain clear-eyed about the losses their sentences

entail. Their discussions of Balzac, Freud, Stendal and Zola

take place in an atmosphere of steady brutality and petty

cruelty. Drug-dealing, murder, and other crimes make up a

regular part of the degradation of the prisoners’

environment. Hikmet’s equanimity with regard to this is, as

usual, remarkable from his first appearance. Kemal describes

how, in his first encounter with Hikmet, the newly arrived

prisoner is greeting old friends in the prison when he is

approached by one “Mad Remzi”. This prisoner, “a 24-year-old

man standing with large bare feet on the freezing cold

concrete floor,” has been relegated to the most destitute

ward, where all the woodwork has been burned for heating,

and where he has gone mad. Hikmet greets him warmly and

listens to his mumblings, commiserating with him over his

new sentence of 30 more years for killing a fellow prisoner

over seven lira. “Of course you’re human. Why do you curse

yourself?” Hikmet exclaims.

As Kemal observes later on, Hikmet, “had an unbounded

affection for the human race. So much so that he made it

into a ‘religion.’” At least once, this unflappable empathy

saves his life. When a gypsy who has been hired to kill him

is impressed with his kindness, he decides to forego the

killing and – addressing him warmly as “my older brother” –

to let him in on the plot instead. In another near-miss, it

is Kemal who discovers that three murderers are planning to

kill Hikmet simply so they will be remembered for something

after their own deaths. “Look at us, what do we do? We go

and take out some schmuck and then get thrown in jail

forever,” Kemal overhears them saying. “But if you murder

this guy, then all the newspapers in the world will write

about you. Then your name will go down in history.”4

Tellingly, when Kemal informs Hikmet, the latter simply

laughs; and, later, when the murderers are themselves

killed, “it was Nazim who was the most sorry for them.” In

his writing during and after his prison term, Hikmet keeps

level sight of the humanity deformed inside an inhuman

social architecture. In one poem, written after his release,

he says of his deepest, personal, “impotent grief” that it

is, “as if … [I] were back in prison/and they were making

the peasant guards/beat the peasants again.”5

In the context of this monotony, steady daily work and study

form a provisional bulwark against despair. Both writers

work diligently, a practice that stays with them after their

respective releases from prison. While in Bursa, Hikmet

translates Tolstoy’s War and Peace for the Turkish Ministry

of Education. He even buys a typewriter – “a 1913 vintage

typewriter weighing half a ton”, as he describes it in a

letter, in order to be able to work faster. The machine is,

he adds, “the only production tool I can forgive myself

possessing on this earth.” His immersion in Tolstoy also

feeds into his poetry, which sometimes reads like a Russian

novel broken up into lines. And when his wife writes to

complain that she might not be able to afford wood to heat

her house during the approaching winter, Hikmet desperately

organises a weaving cooperative to produce cloth and market

it as far as Istanbul. In this, too, his generosity is

evident: he sets aside a share of the profits for Kemal, and

another for his former cellmate and novelist Kemal Tahir.

Six years after Kemal’s release, Hikmet is still sending him

dividends, along with cloth samples to peddle, and arranging

for the purchase and delivery of a rubber sheet following

the birth of Kemal’s second child.

Most luminously, Kemal’s memoir is a tribute to the ways in

which his friendship with Hikmet forms a lifeline for both

writers during and after their prison terms. As Hikmet

writes to Kemal in 1946, “For a man in prison a good friend,

a good comrade, an excellent brother and a creative person

is half of freedom.” Three years earlier, on the eve of his

release, Kemal also struggles to articulate his ambivalence

at leaving Hikmet behind. Just before leaving the prison, he

writes several poems for his teacher. In one, anticipating

the moment of his arrival home in two days time, he writes,

“At that moment … kissing my beloved on her cheeks/you’ll

look at me with your joyful eyes/from within me.”

-

Kemal’s memoir, published three years after

Hikmet’s death in Moscow, also bears witness to the

exigencies of his life during and after prison. While in

Bursa Prison, Kemal takes copious notes, hoping to write an

extensive memoir. But most of these are lost; the pages that

are preserved are appended to the main body of the memoir,

along with two very short stories that Kemal titled

separately. The tone of these notes is sometimes more

emotionally vivid and specific than the memoir itself, which

often descends into slightly vaguer or generalising language

in recounting memories.

Besides the pressures to elide politics from his text, Kemal

was also under constant pressure to support his family. Once

he moved to Istanbul in 1951, he became one of the few

Turkish writers of his generation to make a living solely

from his literary output. His memoir, therefore, bears

traces of somewhat hurried composition. He often forgets the

names of people he mentions, leaving it to the editor to

supply a footnote. And while each chapter is organised

around a particular idea or relationship, there is also a

fair amount of jumpy or meandering recollection.

Structurally, the book is really a pastiche of various

materials in which the memoir itself makes up only half the

content, and is sandwiched between editor Rona’s historical

overview, the remains of Kemal’s notes and Hikmet’s letters

to Kemal. Towards the end of his memoir, Kemal regrets his

lapses of memory after nearly a quarter of a century,

adding, “I am very well aware that I have not been able to

write about Nazim Hikmet as he deserves.” Still,

collectively these materials offer a lively set of glimpses

into the lives of two major writers and a brief but winning

introduction to Hikmet’s lessons on, “how to look at the

world”. In retrospect, it was this gift that Kemal valued

most highly, because, as he wrote in a letter, “The crucial

thing is to know how to look. Only if you know how to look

can you see what you should see. It is this which Nazim has

taught me.”6

In trying to represent the worldview – or really, views –

contained in Bursa Prison in the forties, both writers

learned new strategies of composition, even as they

struggled to survive day-to-day. The unflinching realism of

Kemal’s subsequent novels, with their focus on the

challenges faced by the urban poor, are a testament to this

education. Likewise, in its candid portrayal of both

writers’ efforts to remain human and committed to humanity,

Kemal’s memoir succeeds admirably. As Hikmet wrote to his

protégé in 1949, “whether an individual is in the grip of

hope or hopelessness is a matter which concerns only that

individual. But … a writer who offers no hope has no right

to be a writer.” By reflecting something of Hikmet’s quest

for a mode of seeing that incorporates individual

perspectives into collective progress, Kemal’s memoir

justifies his mentor’s belief that reality is, as Hikmet

insists, “sad, anguished, bitter, twilit, abhorrent,

abominable, contemptible, vile … but not without hope.”

1. Orhan Kemal, In Jail With Nazim Hikmet (London, Saqi

Books, 2010), p. 53.

2. Ibid, p. 12.

3. Nazim Hikmet, Human Landscapes From My Country (New York,

Persea Books, 2002), p. xii.

4. Orhan Kemal, “In Jail With Nazim Hikmet” (London, Saqi

Books, 2010) p. 111.

5. Nazim Hikmet, Poems (New York, Persea Books, 2009), p.

123.

6. Kemal, In Jail With Nazim Hikmet (London, Saqi Books,

2010), p. 38.

Related Tags: Issue V

Previous Article: Foreign intervention in the Middle East

today |